How to pass an airtightness test, Part 2: testing for airtightness

Most newly-constructed buildings in the UK and Ireland must undergo an airtightness test. But how does airtightness testing work, what different types of tests are there, and what do you need to do to get a building ready for testing?

Blower door test.

Airtightness is critical for high performance buildings. As we saw in the first part of this blog post, it is essential for energy efficiency, preventing dampness and mould, and for protecting your building’s structure. Achieving airtightness requires good, simple design and attention to detail.

Whether you are aiming to reach an onerous standard of airtightness like the passive house standard (0.6 air changes per hour), or just trying to meet building regulations, you will probably need to undertake at least one airtightness test.

More likely, you’ll want to undertake multiple tests during the build so you can measure how close you are to meeting your target, and so you can find leaks and fix them before the day of your final test.

The guidance in this blog post is mainly related to airtightness testing of homes and small buildings, as testing large public or commercial buildings can be a more complicated affair.

Also read part 1 of this blog:

Recommended article

How is airtightness tested?

The primary way airtightness is tested is via a blower door test. During a blower door test, a fan is installed in the door or window of the building to be tested. The blower door machine then pressurises or depressurises the building to force air through any cracks or gaps in the building envelope. The amount of air passing through the fan is then measured (more on this below).

Short video showing a blower door fan in operation during a whole-building airtightness test. In this case the fan is facing inwards, indicating the building is being depressurised.

As we explained in part one, the results of a blower door test are given in one of two units — air changes per hour (ACH, also called the n50 value) or air permeability (measured in metres cubed per hour per metre squared, m3/hr/m2, and known as the q50 value).

Testing on the spot

There are also ways to undertake spot tests to check the integrity of particular junctions or hunt down individual points of leakage. These include:

- Smoke pencils/guns, which produce a visible smoke so you can see how air is moving

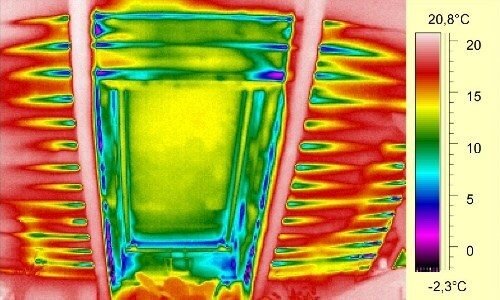

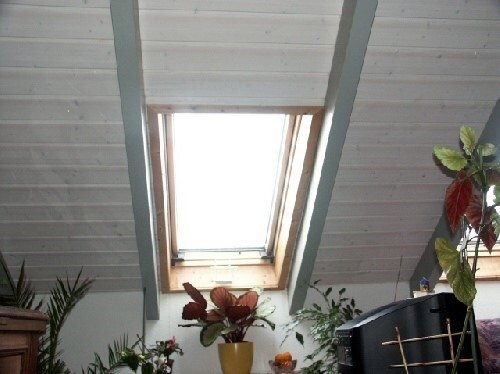

- Thermographic cameras, which show the temperature of different building elements in different colours

- Air velocity metres, which measure air movement at a particular point

Using these while a building is pressurised or depressurised during a blower door test can be particularly helpful in finding leaks.

Infrared image of a leaky roof window during a blower door test, taken with a thermographic camera, and a regular photograph of the same window. (Photo Sönke Krüll, CC BY 3.0)

Planning your airtightness tests

It is generally recommended that you undertake at least one preliminary whole-building airtightness test, prior to your final test, in order to identify any previously unidentified sources of leakage.

This is particularly the case if you are aiming for a very stringent standard of airtightness like the passive house standard. For such high performance buildings, it is often recommended that three blower door tests are undertaken. These tests are normally completed:

- Test 1: As soon as the air barrier is complete, but before any services or appliances are fitted. This may require temporary sealing of window openings etc. This allows you to find any leaks before the air barrier is covered up.

- Test 2: After first fix, when services have been fitted, but before appliances have been installed. It is crucial to achieve an airtight seal around service penetrations etc before they are sealed away. It is also advised that you aim for a significantly better result at this stage than you require, as the air barrier may suffer damage during second fix.

- Test 3: A final acceptance test on practical completion

Get your own mini blower door

Because it’s so important to undertake repeated tests if aiming for the passive house standard, some contractors even have their own small blower door test units, to help make repeated testing easy. These are not intended to replace your primary blower door tests, just to help find leaks and measure the progress of your build as you prepare for your main test.

Preparing for your blower door test

It is crucial that the project team are properly prepared before and on the day of a blower door test. Leading Irish airtightness tester Martin Cooney of Irish Energy Assesors sent us the following list of items that must be checked before an airtightness test:

- the air permeability target for the building

- the result required to comply with building regulations

- the building area and volume must have been correctly calculated from up-to-date drawings

- The weather forecast must be suitable. Wind speed must not be above 6 m/sec (force three) or results will not be reliable

- The building should have power

It is also vital to ensure the building itself is properly prepared for the test. Martin Cooney also advises that the following steps are needed to make sure the building is ready:

- All internal doors are wedged open

- External doors and windows are closed, or openings are sealed if they are not installed yet

- Chimneys are sealed

- Trickle or wall vents are closed but not sealed

- Permanent open vents are temporarily sealed

- Traps are checked for water and sealed if they are not full

- Heat recovery ventilation unit is switched off and ducting is sealed

What happens during a blower door test

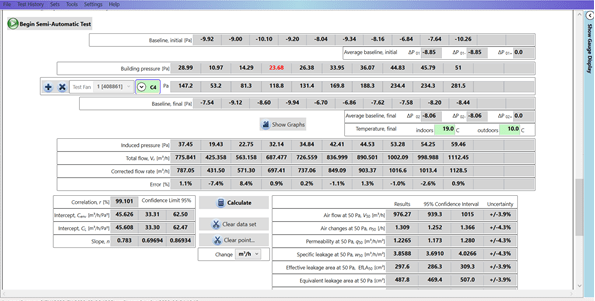

During the test a blower door machine is installed into the door or window of the building to be tested. Once the building is sealed up correctly according to the appropriate testing protocol (more on this below), it is then depressurised or pressurised using the fan, and the amount of air moving through the fan is measured.

Sample test results from blower door pressurisation (Photo: Martin Cooney / Irish Energy Assessors)

It is worth noting that under the latest Irish building regulations, the building must be both pressurised and depressurised, and the same is true for buildings being tested to the passive house standard.

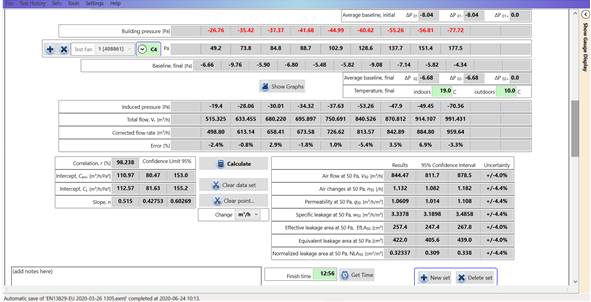

Under UK building regulations only pressurisation OR depressurisation is required. But testing in both directions can help to reveal different leaks — for example depressurisation is particularly good at revealing leaky seals around windows.

Sample test results from blower door depressurisation (Photo: Martin Cooney / Irish Energy Assessors)

Typically, the airtightness tester will perform a series of tests in each direction at intervals between 10 and 60 Pascals of pressure. These are relatively small amounts of pressure — up to about wind speed force five.

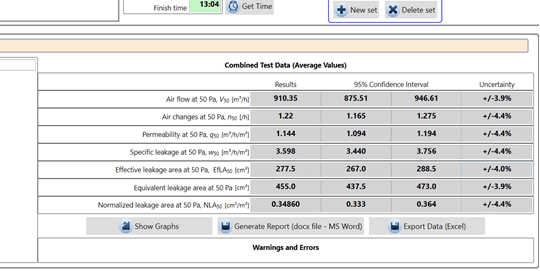

Testing at more intervals (for example, every five Pascals between 10 and 60) will yield a more accurate result. The result at 50 Pascals can then be extrapolated from these results, and if the property has been both pressurised and depressurised, the average of the two results is taken as the airtightness test result.

Combined pressurisation and depressurisation figures, giving final result of 1.22 ACH (n50) and 1.144 m3/hr/m2 (q50) at 50 Pascals. (Photo: Martin Cooney / Irish Energy Assessors)

Testing procedures and regulations

Important note: there are different airtightness testing protocols, depending on which testing standard is being used.

The protocol for undertaking airtightness tests has generally been based on the EN (European) standard EN 13829:2000, but interpretations of this can vary from country to country. There is a newer standard, EN ISO 9972:2015, but many building regulations, including those in the UK and Ireland, still refer to EN 13829:2000.

Both standards are quite similar but there are some minor differences, such as with how the building volume is calculated.

Don’t worry, just prepare!

Overall, with a little preparation there is no need for the day of your airtightness test to cause any stress or anxiety on site, especially if you have designed and built with airtightness in mind from the outset.

Just make sure you are properly prepared by:

- Knowing your targets. What airtightness score must you achieve to meet the building regulations, and what is the client’s airtightness requirement for the building?

- Testing regularly. Undertaking multiple whole-building airtightness tests during construction, as well as spot-tests to locate individual leaks, will make it easier and less expensive to remedy faults than leaving it all until the end.

- Preparing for the test. Make sure your airtightness tester has all of the information they need well in advance of the test, and that you have prepared the building for the test in accordance with their instructions.

Did you like this article? In this 12 minutes blog post, we talk about how to design and build for airtightness from the start.

Recommended article

Lenny Antonelli

Lenny is a journalist who covers the environment and sustainability. He has been writing about the built environment for over a decade, and is deputy editor of the sustainable building magazine Passive House Plus.