2 reasons why airtightness in Part-L must be revised

The UK government's recent proposals to revise Part-L regulations fall short, says the industry. These changes could double heat loss and increase building costs, making energy and emissions targets harder to meet.

The UK government was recently criticised by its own climate advisors for failing to update the building regulations, which were described as ‘not fit for purpose’.

One major omission is the failure to tighten airtightness targets.

Airtightness targets in the England building regulations have not changed since 2013. The government’s proposed target of 5m3/m2.h – due in 2022 – is still not good enough, industry says. They could lead to double the heat loss compared to current industry best practice, calculations show.

Numerous people in the industry have warned that homes built to the proposed 2025 fabric standards may require retrofit in just a decade or two. Otherwise we will fail to meet our zero-carbon target for 2050.

In June 2021 the UK Committee on Climate Change (CCC) made its annual report to MPs on the government’s progress towards climate targets.

Buildings account for 29% of all UK emissions: more than half of the total is direct emissions from gas or oil, being burned for heat. Despite the prominence of buildings in the UK’s total emissions, The CCC rated the department responsible for construction standards, MHCLG (Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government) especially poorly.

Progress on improving the regulations has fallen short

Buildings standards are “not fit for purpose”, and progress on correcting them had “fallen short”, the report said.

The English building regulations for energy use in buildings (Part L) have not been updated since 2013. The situation in the other UK nations is similar. In 2019 the government released its initial proposals for updating Part L (England) in 2025 – the so-called “Future Homes Standard”. MHCLG claimed the proposals would “put us on the right path to achieve our net zero target”.

In spring 2021, the government published a further set of proposals- the Future Buildings Standard. This included proposals for an interim upgrade of standards, due in June 2022. There were some welcome proposals, including that every new house should have to undergo its own air leakage test. (Currently on a large development as few as 1 in 40 homes will be tested.) But the overall lack of ambition was greeted with disappointment.

The airtightness and ventilation targets are wasteful, out of date – and out of step

The proposed ‘reference building’ (which sets an overall emissions target to match or beat) proposed an airtightness of 5m3/m2.h at 50Pa, and natural ventilation. This is the same permeability and ventilation strategy as 2013. The airtightness backstop is proposed to be 8m3/m2.h. This is barely better than the current legal limit of 10, which was introduced as long ago as 2002.

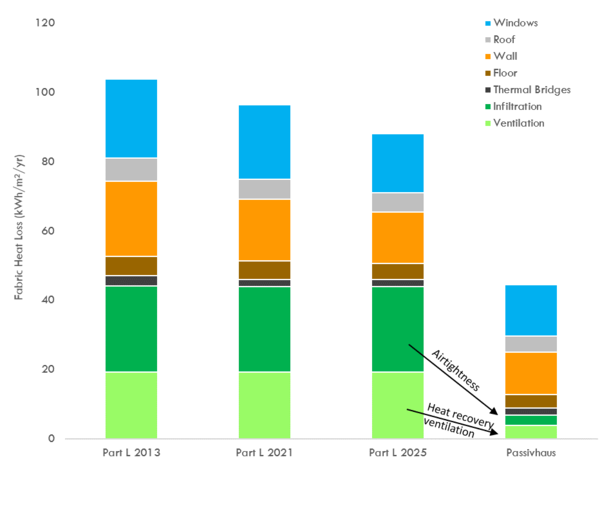

Calculations by Thomas Lefevre of sustainability consultancy Etude [see graphic] show that a building to the proposed 2025 “reference” standard would have double the heat loss versus a Passivhaus. The difference is almost all due to high levels of airtightness in combination with heat recovery ventilation in the Passivhaus. The elemental U-values of each are very similar.

Contribution of airtightness and MVHR to fabric efficiency. The Part L “reference building” has a fabric heat loss of almost 90 kWh/m2/year. The Passivhaus, which has very similar u-values, has fabric heat loss of only 40kWh/m2/year. The biggest saving, (around 25kWh.m2) is down to the excellent air tightness (~0.6 m3/m2.a). An additional 15 kWh/m2 is saved by the use of MVHR. Together, these measures cut fabric heat loss by around half, versus a “Future Homes Standard” build. Graphic courtesy of Etude.

Many European countries set higher targets and have been achieving them for some years. For example, homes in Finland must achieve an air permeability minimum of 4 m3/m2.h; homes Germany and Austria are expected to have an airtightness of 3ach @50Pa (natural ventilation), and mechanically ventilated buildings, 1.5 ach. Sweden, Lithuania and Switzerland set even higher standards.

In Ireland the standards are also already higher than those proposed by the UK government. The 2019 Irish Building Regulations set a backstop permeability of 5m3/m2.hr. Buildings are generally expected to achieve a result of 3 m3/m2.hr or better. Even as far back as 2011, the Irish air permeability maximum was 7 m3/m2.h at 50 Pa – tighter than the backstop the UK government is proposing for 2022!

The Irish construction industry has had no problem rising to the challenge: in 2019, the average air permeability there was down to 2.85 m3/hr/m2.

Proposals are a long way from ‘world class’

Thus, the current proposals won’t even bring the UK in line with established practice elsewhere. As CIBSE commented in its consultation response: “This is quite far from the ‘world class’ levels of energy efficiency intended for the Future Homes Standard.”

SIGA engineer Stan Admiraal shares this view:

One thing that really jumps out from these proposals is that the airtightness – of both the backstop 8m3/m2.hr and the notional building 5m3/m2.hr – really doesn’t go far enough.

He adds:

This is something that not only manufacturers like us are saying, but also something the majority of people responding to the consultation said.

In their response to the first, 2019, stage of the Future Homes Standard consultation, MHCLG admitted that almost 70% respondents said the ambitions on fabric efficiency were not demanding enough. Just 10% said they were OK. Similarly, the majority of respondents thought the backstop of 8m3/m2.h m3/hr/m2 was too leaky.

The government admitted that people warned them their ambitions were so poor, that buildings built in 2025 would need retrofitting. “There were calls for the Government to push fabric standards even further on the basis that the Government’s legally-binding target of net zero emissions by 2050 required urgent action,” MHCLG wrote. “There was a particular concern that the fabric standards proposed may require further retrofit work at a later time in order to meet the net zero emissions target.”

This comment could be seen as ironic, given that in the introduction to the very same document MHCLG themselves state:

Energy efficient, low carbon homes will become the norm. It is significantly cheaper and easier to install energy efficiency and low carbon heating measures when homes are built, rather than retrofitting them afterwards.

What do British builders think about the Part L update?

In 2019, the government tried to justify their lack of ambition by saying: “Not all home-builders are ready to build to higher fabric specifications yet”.

Yet the government admitted that the “target” airtightness was already achieved by the construction industry every day: “it was noted that 5m3/m2.h is the current average amongst new builds.” Many UK construction teams regularly achieve 3,2 or, on Passivhaus sites, less than 1 m3/m2.h.

I spoke to a couple of practitioners whose buildings attain these levels, and asked them what it would take for all home builders to be “ready” to target airtightness of 3m3/m2.h or better on a regular basis.

Ian Pritchett is Managing Director of Greencore Construction, who specialise in very low energy, “climate positive” houses, using natural materials. Architect Alan Budden is founder and director of Eco Design Consultants, who specialise in low energy and Passivhaus homes.

Both felt that high levels of airtightness were perfectly achievable. What was needed was the right mindset. Targets should be set clearly from the outset, and designers need to understand how to support airtight construction on site.

Airtightness doesn’t have to be difficult!

Ian Pritchett has little patience for the excuse that airtightness is “too difficult”. “I think permeability tighter than 3m3/m2.hr can be achieved quite easily by a novice. The key requirements are understanding and care,” he said.

I often describe achieving good airtightness as like learning to drive a car or fly a plane. It seems really difficult until you know how to do it. Once you know how to do it and you do it regularly, it is easy.

Alan Budden agreed that good airtightness was a matter of approach – and skill and awareness on the part of designers.

Eco Design Consultants regularly achieve very high airtightness on their builds, including 0.6 ach @50Pa (roughly equivalent to 0.6m3/m2.h) for Passivhaus builds.

“To get good airtightness, you do need a quite different approach,” Alan Budden said. “But if a proper airtightness target was set in the regulations, it’s not as if the construction industry couldn’t work out how to do it. There’s no reason not to just get on with it.”

Alan’s point was illustrated by a recent site test result, shared by Chris Worboys from Etude. This was on a multi-residential project that is aiming for high levels of airtightness. The developer’s team achieved an air permeability very close to 1 m3/m2.hr at first go – even though, as Chris understands it, the team had little or no experience of targeting this level of airtightness.

As Chris’ colleague Thomas Lefevre commented:

We think that good airtightness is less hard than people fear!

Save money by building airtight

Thomas Lefevre is one of many who point out that the failure to embrace airtightness can lead to unnecessarily expensive construction. At a joint Passivhaus Trust and LETI event to discuss MHCLG’s proposals, he pointed out that:

“Airtightness is a cost-effective way to get high energy performance.”

Alan Budden agrees. He is dismayed by the wastefulness of trying to tackle building emissions without using airtightness and MVHR.

Airtightness can really save money. It saves money on extra insulation and on more expensive fixings… And you get a better building: it’s cheaper, the quality is better, and you get fewer call-backs.

As SIGA’s Stan Admiraal says:

Building airtight gives you results with a smaller impact on the environment: less manufacturing, less transport of bulky insulation materials.

An airtight building enables construction teams to reach emissions and energy targets without the need for complex insulation detailing.

You can’t separate airtightness and ventilation

As well as suggesting that “not all house builders are ready” for high airtightness, the other reason given by the government for their low ambitions, is to permit continued use of natural ventilation.

Once again, the government position lags behind the respondents to their consultation. The government reported that “Across the responses we received, it was argued that all new homes should have mechanical ventilation with heat recovery.”

However the government response was only to say: “we will continue to provide guidance for natural ventilation…on the basis that this system type still represents a significant proportion of the UK market.”

Yet the fact that this form of ventilation is common is likely only to be because it has been permitted – and because it is cheap. The government’s own research has shown that in practice natural ventilation does not deliver good air quality. Other research has shown that leaks in the fabric do not contribute reliably to good indoor air quality, either.

Failing to require whole-house heat recovery ventilation as standard in new homes has led to the depressing practices of deliberately limiting – or worse, deliberately worsening – the airtightness of a new home. The building is made less efficient on purpose, simply to avoid having to upgrade the ventilation.

Alan Budden, like many others in the industry, finds this wastefulness shocking. “One of the most ridiculous things is deliberately making building less airtight because of concerns about ventilation.”

“Honestly I think we should just be installing MVHR regardless. Even if you don’t get the full efficiency benefit at a lower airtightness, you get all the other benefits. And then you can’t accidentally make the building “too” airtight.

Stan Admiraal agreed “If all buildings need mechanical ventilation, then building airtight is a reward and not a punishment.”

Kate de Selincourt

Kate is a writer and researcher specialising in sustainable and healthy building and retrofit.